These are notes used for lecturing ECSE 507 during the Winter 2024 semester.

Please note that these notes constantly evolve and beware of typos/errors.

These notes are heavily influenced by Boyd and Vandenberghe’s text Convex Optimization.

I appreciate being informed about typos/errors in these notes.

Click each subject to unfold.

Introduction

General Problem

Interested in solving and studying minimization problems subject to constraints:

-

are problem parameters;

-

is the objective function and

usually interpreted as cost for choosing

;

-

is a constraint set often described “geometrically”.

Example 1. Design Problem Interpretation

Let=scalar-valued design variables

(e.g., dimensions of manufactured object, yaw and pitch of jet).= penalty for choosing design

(e.g., cost in material, energy, time, deviation from desired path).= design specifications

(i.e., allowable/possible values for).

E.g.,specifies minimum and maximum design values.

Problems With Structure

General optimization problems can be numerically inefficient to solve or analytically difficult, unlessIdentifying nice structure/properties of problem

Examples of nice structure:

E.g.,

If

Linear Programming

Simplest case:Notation: if

means

for

.

Linear program: given

Positives of linear programming:

- Conceptually simple: relies heavily on linear algebra

- There are classical numerical methods which are often very efficient.

- If

is local minimizer of

on

, then it is automatically a global minimizer on

.

- Can sometimes approximate smooth problems linearly; however, usually can only give “local” results.

(E.g.,for

.)

Shortcomings of linear programming:

- Many applied problems are not linear.

- Many problems may not even be (suitably) approximated by linear programs.

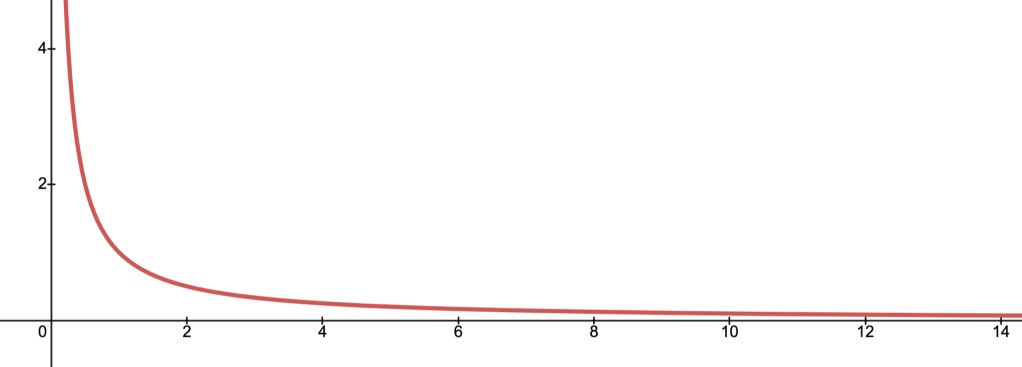

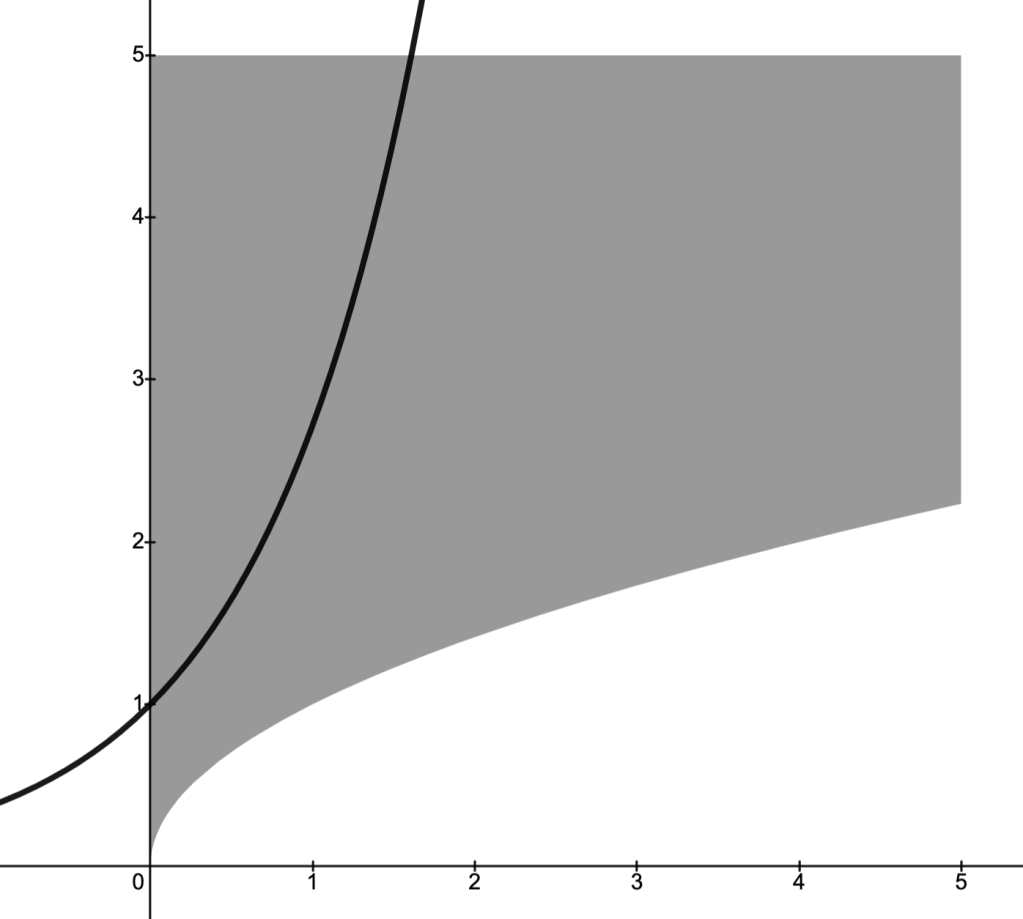

E.g., the “barrier”

is better approximated by the a “logarithmic barrier” of the formthan any linear function.

Convex Optimization

Convex optimization problem:This is the main focus of the course.

Positives of Convex Optimization:

- Relatively conceptually simple.

- Still often have efficient, albeit more sophisticated, numerical methods.

- Many applied problems may be recast as or approximated by convex optimization problems.

- If

is local minimizer of

on

, then it is automatically a global minimizer on

.

Shortcomings of Convex Optimization:

Example (Least Squares)

A standard and ubiquitous kind of convex optimization problem is the least squares problem.This problem takes the form:

is some norm

a matrix

a fixed vector

is the (convex) objective function

are convex.

Optimal Control

Let-

be functions

.

-

is the time derivative of

.

-

are assumed to be given;

-

we think of

as being the state of some system at time

;

- we think of

as an input we are allowed to choose to dictate the evolution

of

; i.e.,

“controls” the system;

- When

, the system experiences “feedback.”

-

the goal: choose control law

so that

is as “desirable” as possible.

Example: Optimal Control Problems

Optimal control problem: choose the “best” controlTypically “best” and “desirable” are determined by size/cost of

Rough Outline of Course

- Part 1: Basics of Convexity and Convex Optimization Problems.

- Part 2: Applications of Convex Optimization Problems.

- Part 3: Algorithms for Solving Convex Optimization Problems.

- Part 4: Topics in Optimal Control.

Convex Geometry

Convex Sets

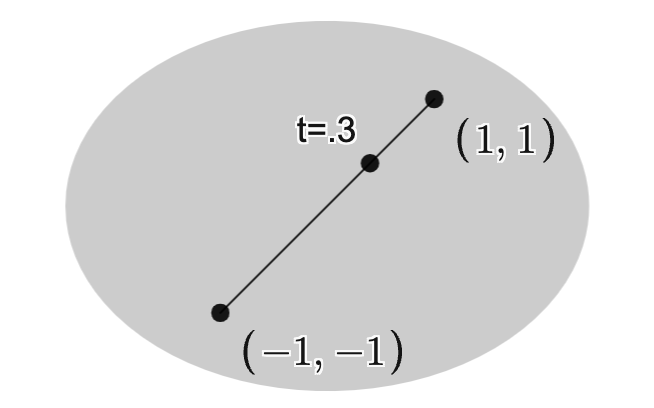

Convex set: a subset

for all and

, there holds

.

Examples: some standard convex sets.

- Closed or open polytopes in

.

E.g., the interior of a tetrahedron. - Euclidean balls, ellipsoids.

- Linear subspaces and affine spaces (e.g., lines, planes).

- Given a norm

on

, the

-ball

with centerand radius

is a convex set.

Recall: a norm satisfies-

for all vectors

;

-

for all vectors

and scalars

;

-

iff

.

-

Affine Subsets

Affine subset: A subset

For all and

, there holds

.

N.B.: An affine subset is just a translated linear subspace:

“a linear space that’s forgotten its origin”.

Example 1.

LetThen any translation or rotation of

Example 2.

If(

Cones

Cone: A subset

For all and

, there holds

.

Proposition.

Proof.

Step 1. ( )

)

Suppose Want to show:

Step 2.

Being conic impliesStep 3.

Being convex impliesStep 4. ( )

)

Suppose Want to show:

Step 5.

Step 6.

Convexity follows from takingIndeed:

Examples.

- Hyperplanes

with normal

,

halfspaces,

nonnegative orthantsare all convex cones.

(Here,if

for

.)

-

Given a norm

on

, the

-norm cone is

which is a convex cone in,

.

- See “positive semidefinite cone” below.

Polyhedra

Polyhedron: Any subset

Thus,

N.B.: Introducing equality constraints can be used to reduce dimension.

Positive Semidefiniteness

Symmetric matrix:

a matrix

Positive semidefinite matrix:

Equivalently,

If

If

Set of symmetric positive semidefinite matrices:

Positive definite matrix:

Equivalently,

If

If

Set of symmetric positive definite matrices:

Example 1

LetSince

To see

with

Example 2.

LetSince

To see

Example 3.

LetOne can conclude

To see it directly, compute

Example 4.

LetWe can conclude

Positive Semidefinite Cone

Proposition 1.Proof.

Step 1.

is a vector space:

is a vector space:

if

.

Step 2.

:

:

since

Counting the number of bold entries shows

Step 3.

is a convex cone:

is a convex cone:

For

,

By the proposition in Convex Geometry.Cones, we conclude the desired result.

Proposition 2.

and

.

Proof.

Step 1.

Let

recalling that

Step 2. (Case  )

)

First compute

for all

iff

.

Can thus conclude (in case

for all

iff

.

Step 3. (Case  )

)

Completing the square gives

for all

iff

and

.

N.B.: strictly speaking,

Step 4.

Putting Steps 2. and 3. together, we conclude:

and

.

Separating Hyperplanes

LetSeparating hyperplane: a hyperplane given by

Thus,

Separating Hyperplane Theorem. If

Supporting Hyperplanes

Let

.

Equivalently,

(Here:

Hulls

LetConvex hull:

the set

.

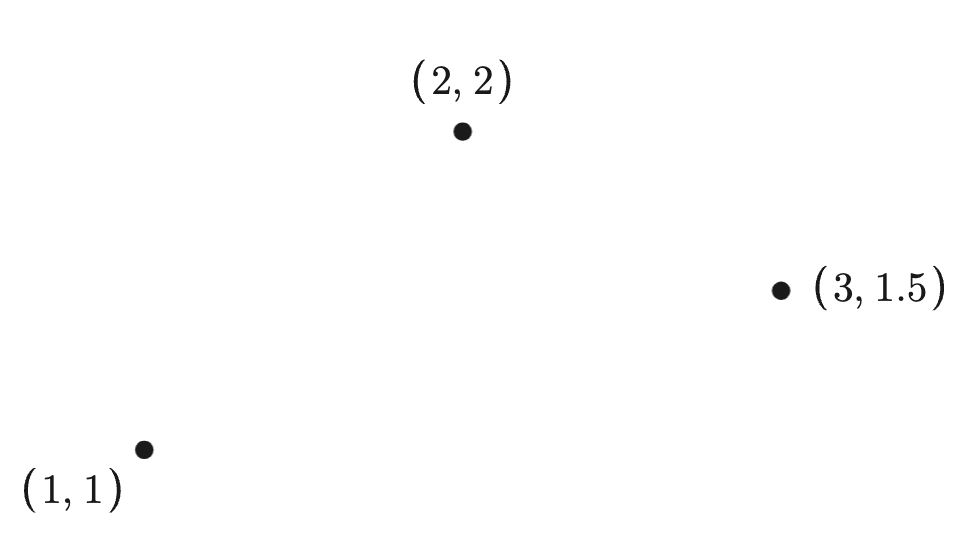

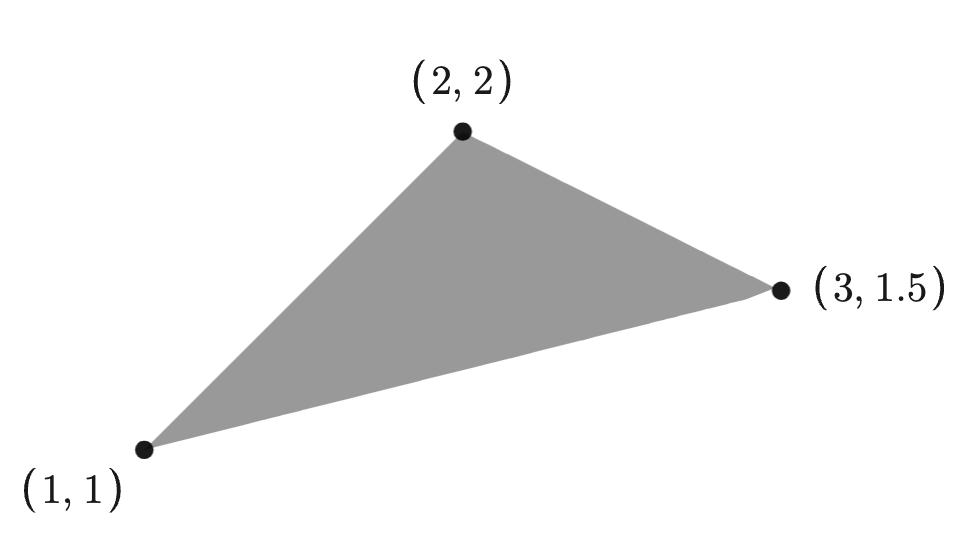

Example: The images below depict a set of three points and its convex hull.

Affine hull:

the set

.

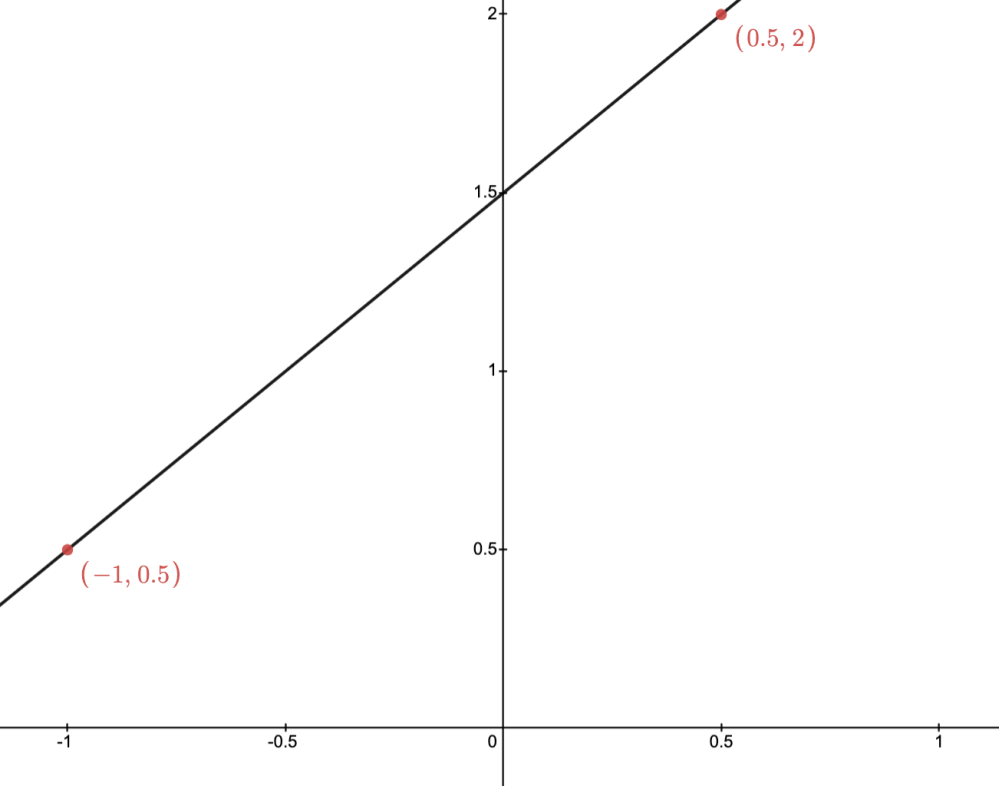

Example: The images below depict two points and their affine hull.

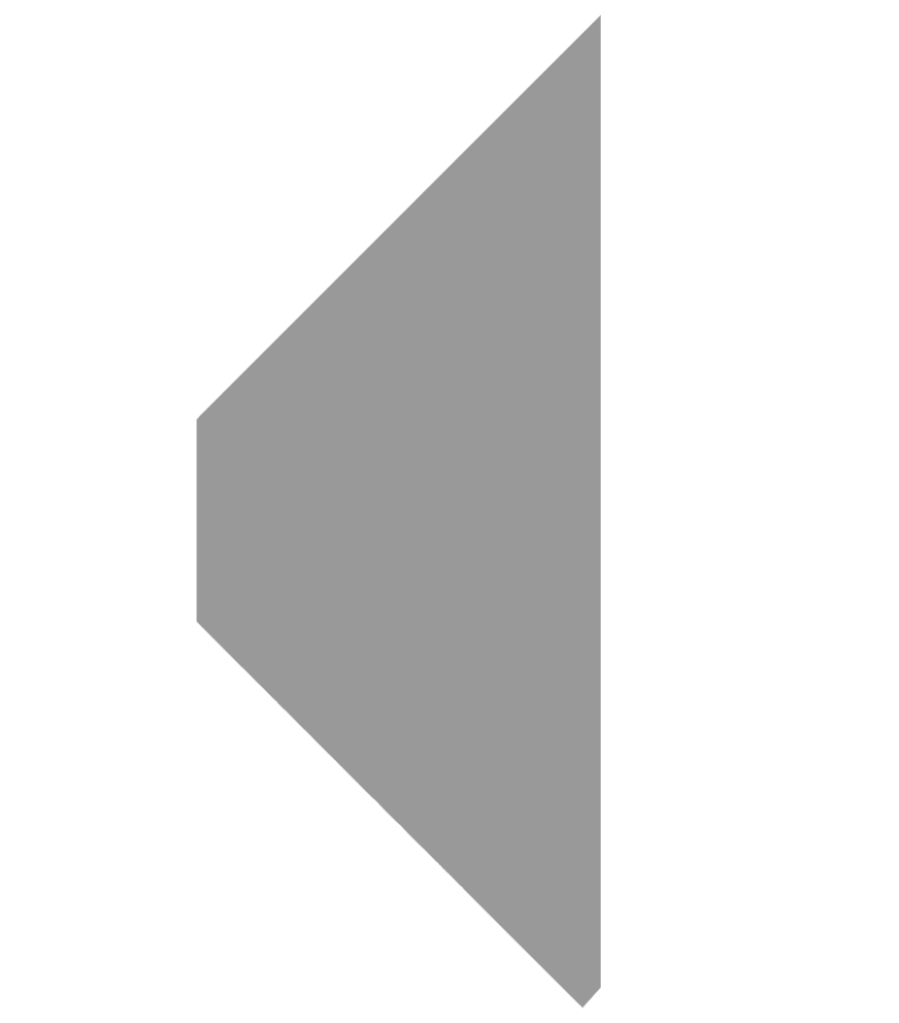

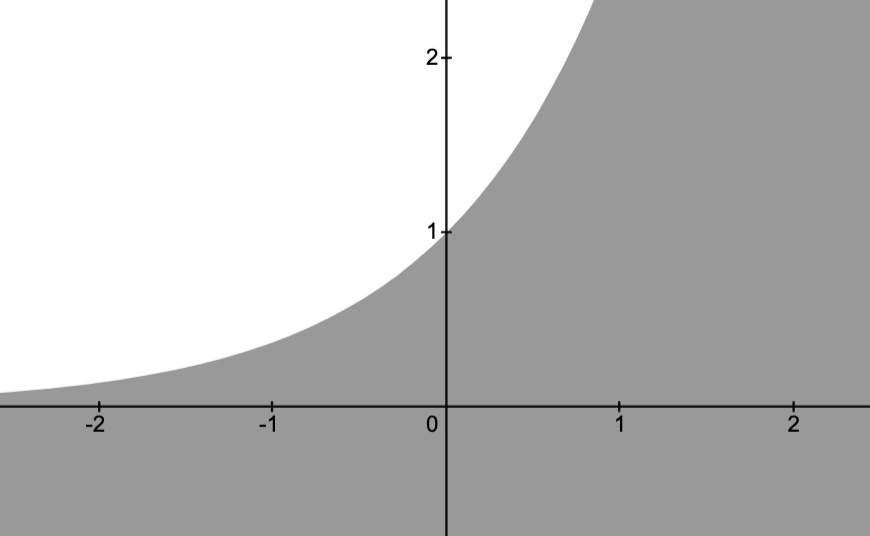

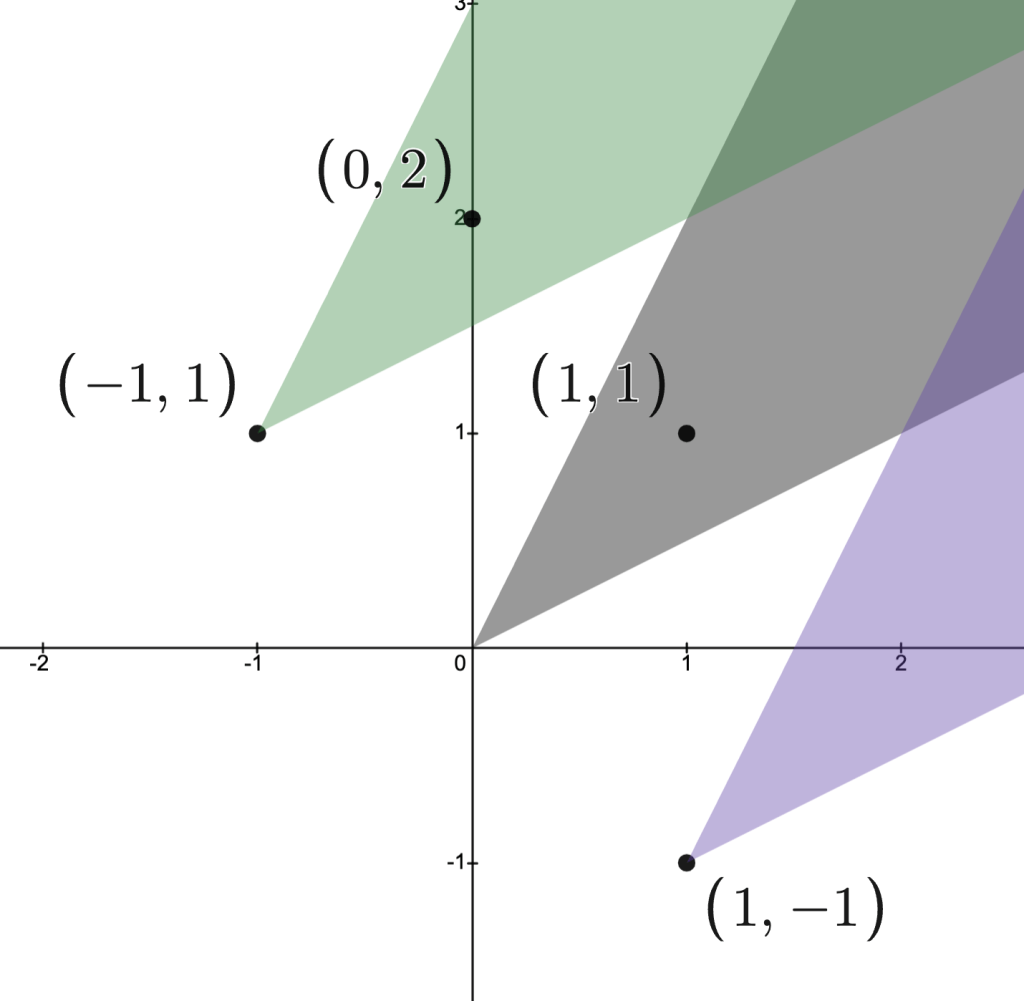

Conic hull:

The set

.

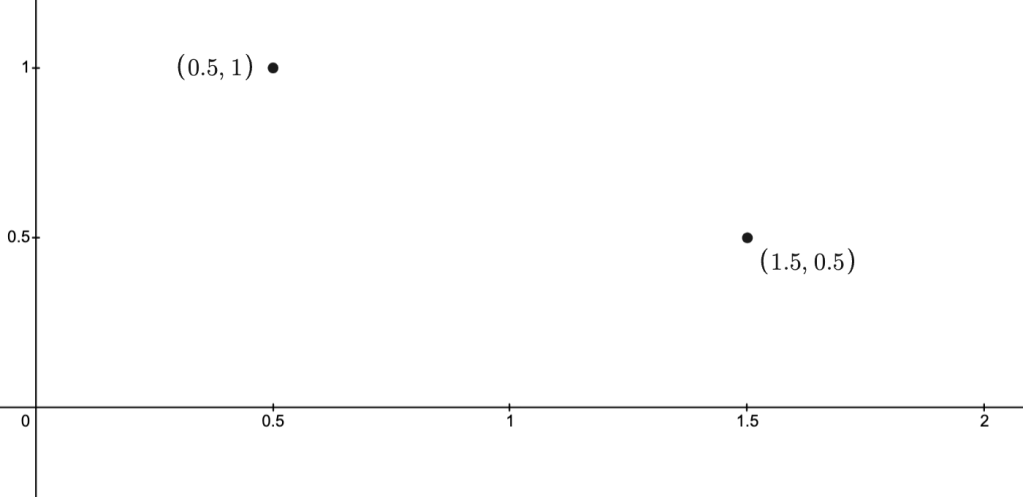

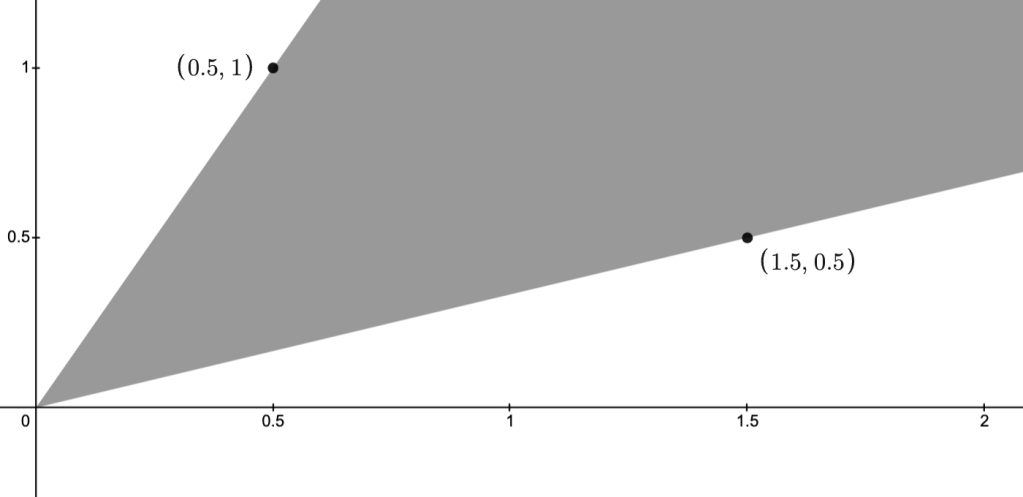

Example: The images below depict two points

Details

To see that the conic hull really is the shaded region, note that, by takingThus, it contains all line segments connecting any two points on the nonnegative rays

N.B.:

- Conic hulls are convex cones.

-

Taking the “___ hull” of

does indeed result in a “___” set.

-

The “___ hull” is a construction of the smallest “___” subset containing

.

Generalized Inequalities

Proper cone: a convex cone-

is closed (i.e.,

contains its boundary)

-

has nonempty interior

-

.

.

.

Examples

-

(CO Example 2.14)

If, then

is the standard componentwise vector inequality:

N.B.:.

is the standard inequality on

.

-

(CO Example 2.15)

If, then

.

-

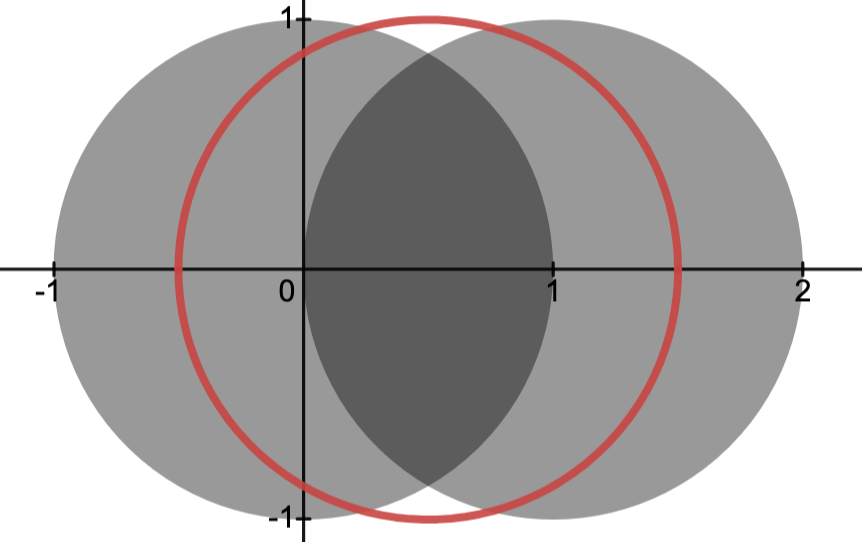

Let

Then.

is a proper cone.

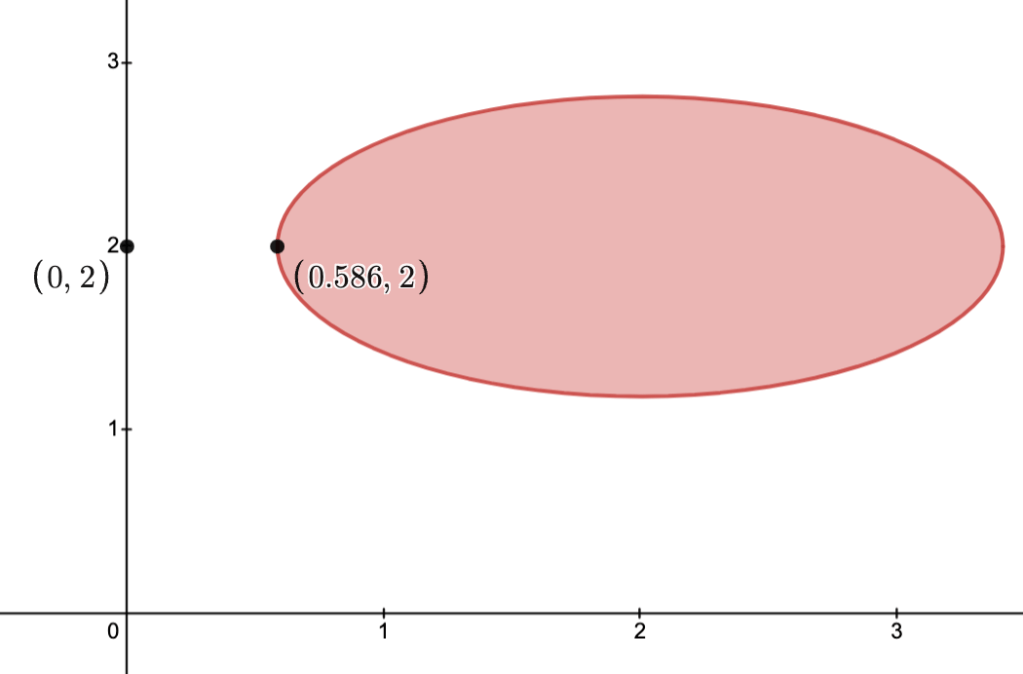

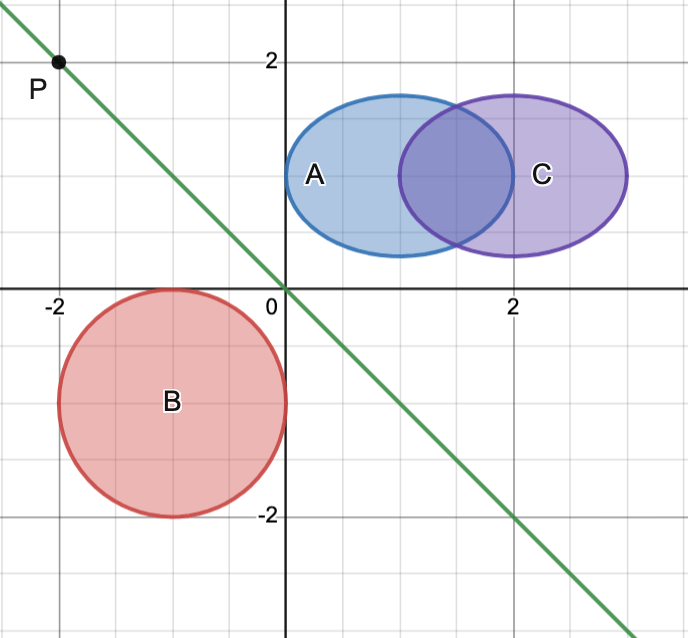

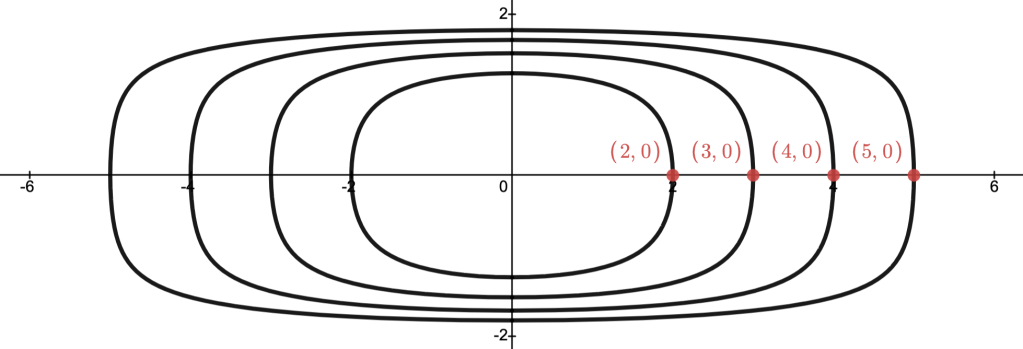

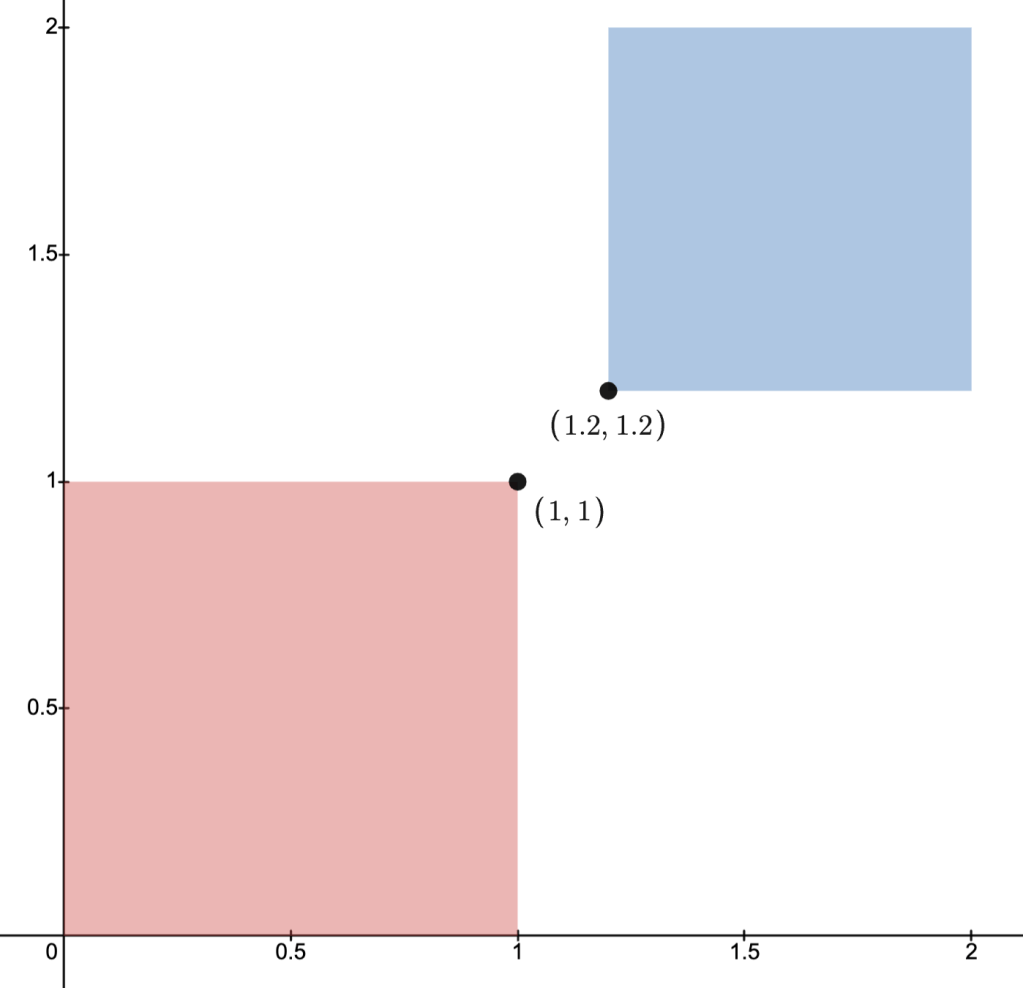

In the image below:-

is the cone with vertex

.

-

The cone with vertex

depicts those

with

.

-

The cone with vertex

depicts those

with

.

, and so

, as indicated in the image.

Moreover,and

are not comparable.

-

Convex Function Theory

Conventions and Notations

-

Writing

always means a partial function with domain

possibly smaller than

.

“Function” will mean “partial function.” - If

, we may work with the extension

given by

It is common to implicitly assumehas been extended and to write

for the partial function

and its extension

.

-

Given a set

, its indicator function is

- We write

Convex Functions

LetStrict convexity:

for all

.

Remarks.

- It is instructive to compare convexity/concavity with linearity and view the former as weak versions of linearity.

- It is common to extend the definition of convexity to extended functions, i.e., those of the form

.

For example, the indicator functionis convex in this sense.

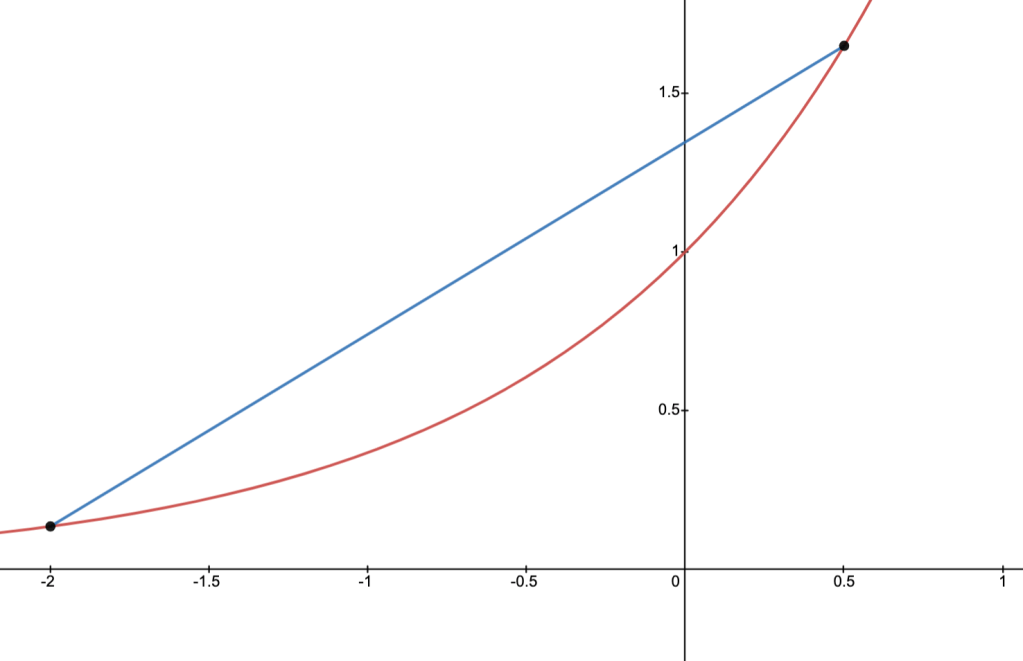

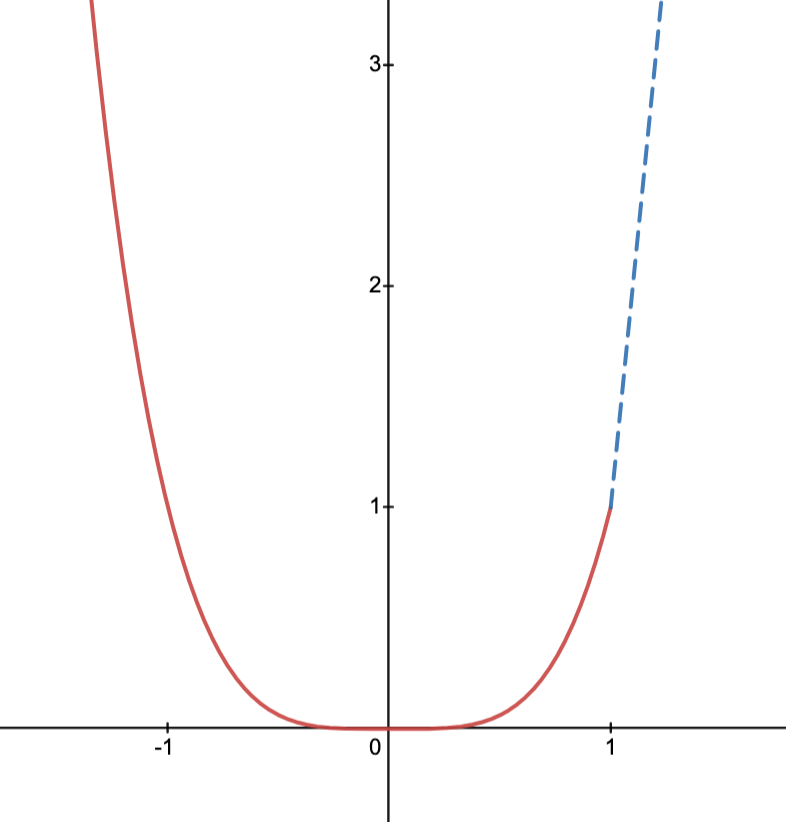

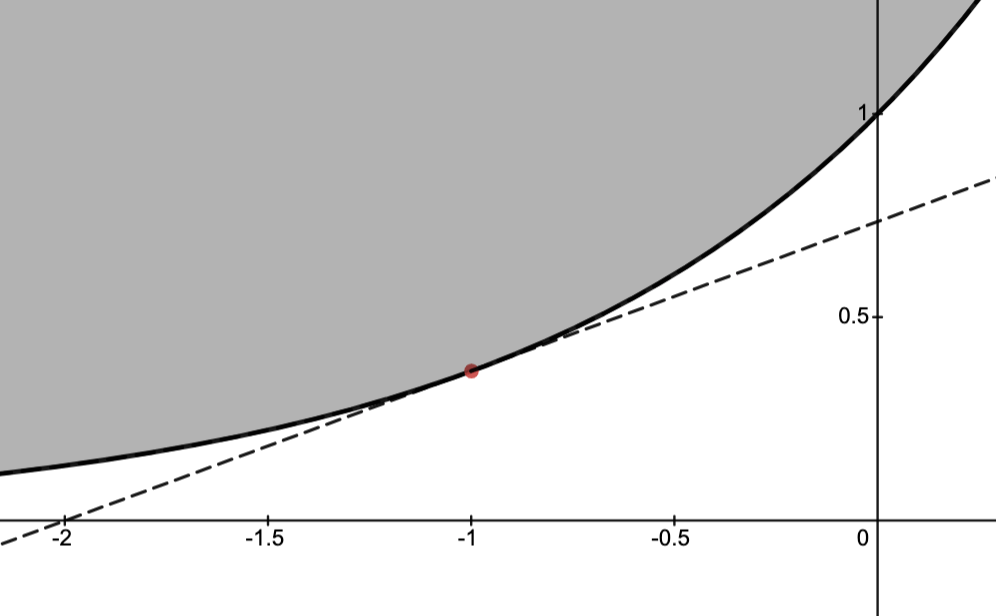

To give insight, consider the image below, where the thick line is the “graph” ofand the dashed line is the “secant line” connecting the points

to

for any

.

Examples

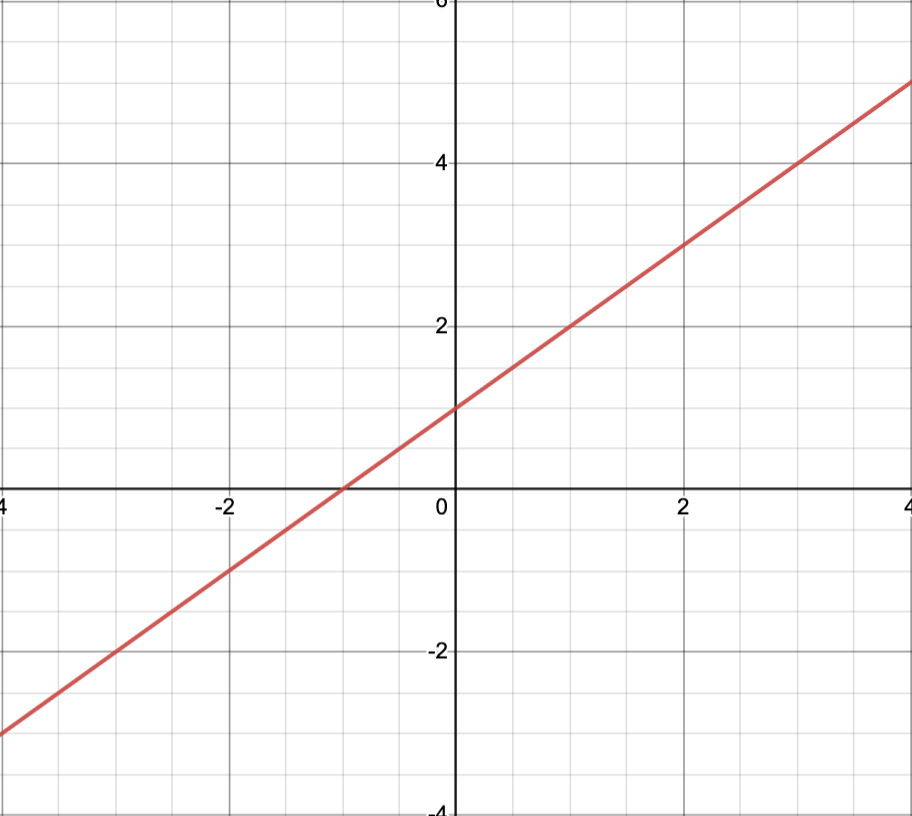

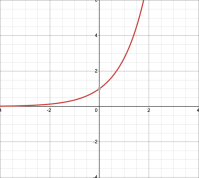

- All linear functions are convex and concave on their domains.

-

is convex on

.

-

is convex on

for

.

-

is convex on

for

or

and concave for

.

-

is convex on

- If

is convex, then its indicator function

is convex (in the extended value sense).

One Dimensional Characterization

Proposition. Let

and

,

.

Proof.

Step 1.

First note thatStep 2. ( )

)

Suppose Then, for

Step 3. ( )

)

Suppose now that each Fix

We want to show

.

,

Since

First Order Characterization

Proposition. If

.

Proof (sketch).

We prove it in caseThroughout, let

Step 1. ( )

)

If

Step 2. ( )

)

Supposing

Remarks.

-

For fixed

, the mapping

is affine whose graph is a hyperplane passing through the point.

Therefore, the inequalitymeans this hyperplane is a tangent plane at

of the graph of

lying under the graph of

.

In fact, this plane is a supporting hyperplane of the epigraph

at the point.

-

The affine mapping

is just the first order Taylor approximation of

at

.

Thus, differential convex functions are such that their first order Taylor approximations serve as a global underestimators of.

Second Order Characterization

Proposition. If

.

Recall: if

Proof (sketch).

Step 0.

The proof is a little more involved, so let us just give two intuitive justifications.Justification 1.

The second order Taylor approximation gives

The first order approximation from Convex Function Theory.First Order Characterization then implies convexity.

Justification 2.

Another intuitive justification is thatRemarks.

-

Recall: for

, there holds

-

for all

implies

is strictly convex.

Converse is false sinceis strictly convex.

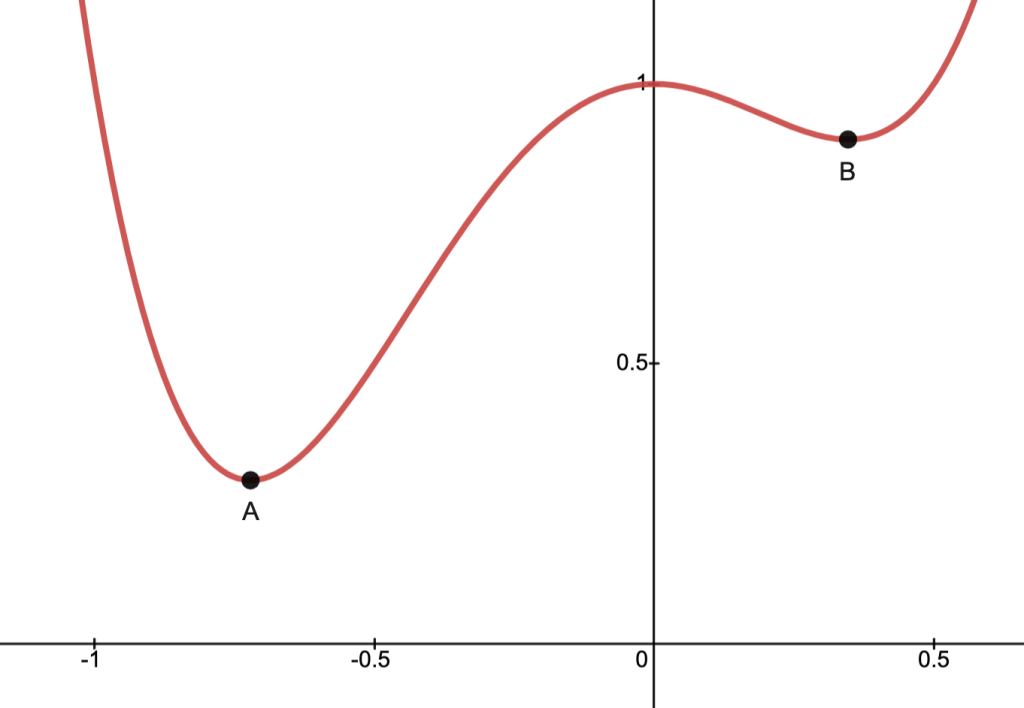

Level Sets

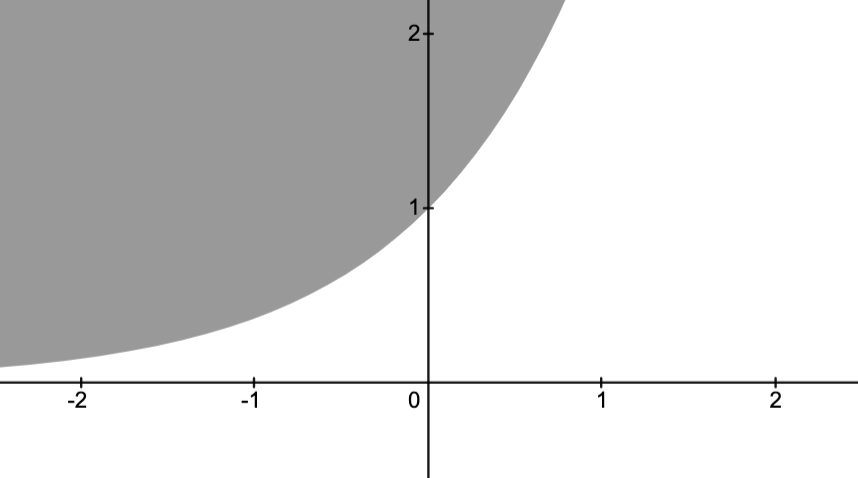

Fix a function -Sublevel set:

-Sublevel set:

the set

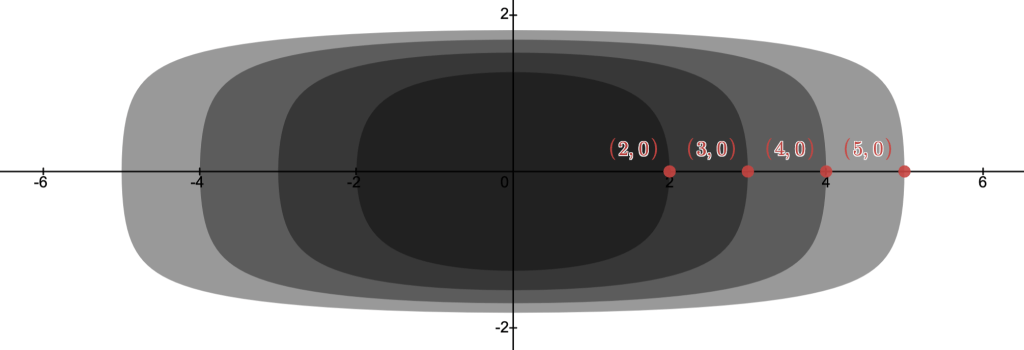

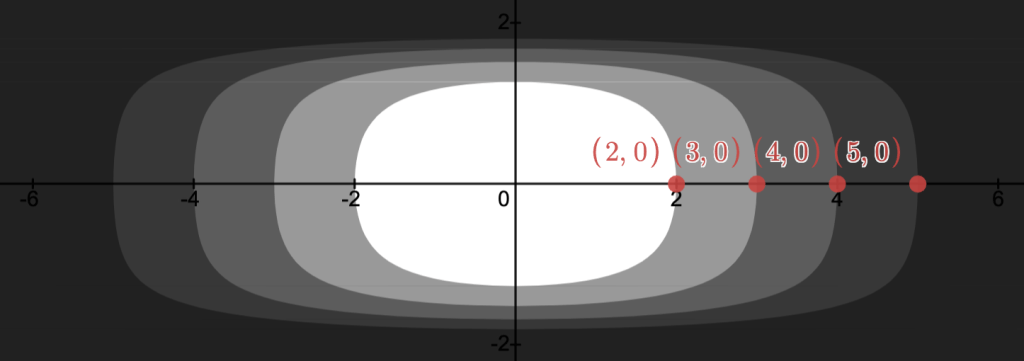

Each shade of gray indicates a new sublevel set and of course

-Superlevel set:

-Superlevel set:

the set

.

Each shade of gray indicates a new superlevel set and of course

Proposition. If

Equivalently, if

Proof.

Want to show:If

and hence

Graphs

Fix a functionProposition.

Equivalently,

Proof. (sketch)

We consider the caseStep 1. ( )

)

Suppose If

Let

(If at most one intersection point exists, then it is easy to see that the line connecting

By convexity of

This shows

Step 2. ( )

)

Suppose now Let

Then

But convexity of

This is enough to conclude

Convex Calculus

The following list details some operations and actions that preserves convexity.The main point: to conclude a function

N.B.: Conclusions only holds on common domains of the functions.

Conical combinations:

convex and

convex.

Weighted averages:

convex in

,

convex.

Affine change of variables:

convex,

,

convex.

Maximum:

convex

convex.

Supremum:

convex in

for each

convex.

Justification.

For

Example.

Let

Thus

Infimum:

convex in

convex

finite for some

convex on

.

Fenchel conjugation

LetFenchel conjugate:

N.B.:

;

Intuition.

SupposeFor a given unit price

.

N.B.:

Thus,

Viz.: the

The tangent line through

Lastly, note that the

Remarks

-

Often

is just called the conjugate function of

.

-

Since

is the supremum of a family of affine functions,

is always convex, even if

is not.

(Follows from Convex Function Theory.Convex Calculus. - If

-

is convex

-

is a closed subset of

,

.

-

Example.

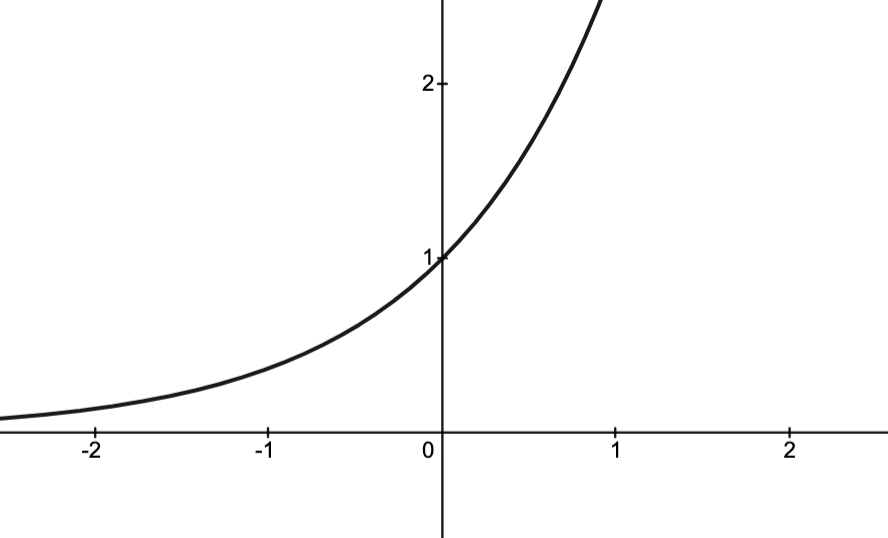

We will compute the conjugate function of

Thus, let

Case  :

:

as

.

.

Case  :

:

Compute

Case  :

:

Compute

,

Conclusion:

Since

for

,

Legendre Transform

LetThen, the Fenchel conjugate

Proposition. If

.

Proof.

Step 1.

Let

.

maximizes

iff

Step 2.

Using Step 1. and

iff

maximizes

.

Step 3.

Letting

,

Example 1.

Let

,

.

; i.e.,

.

,

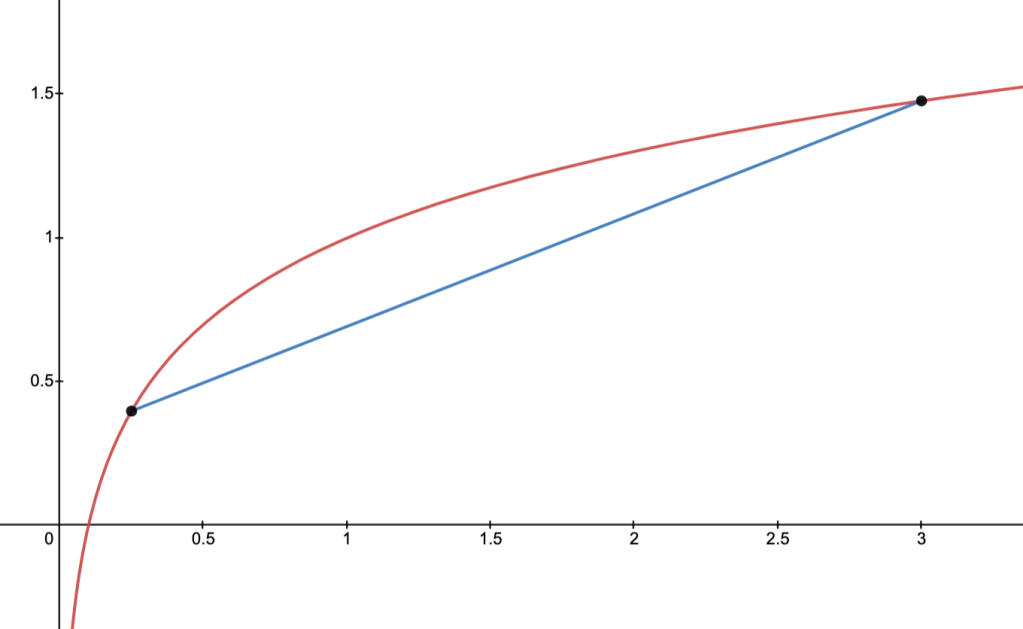

Example 2.

Fix

.

Step 0.

Observe-

is convex:

(Justification)

Consider case.

Let.

Thus.

Easy now to see.

implies

is invertible since then

.

Step 1.

Using

Step 2.

LetBy preceding proposition and Step 1., there holds

Other Notions of Convexity

There are two other important notions of convexity that we will return to if needed.Let

Quasiconvexity:

Features:

- Quasiconvex problems may sometimes be suitably approximated by convex problems.

- Local minima need not be global minima

Log-convexity:

for all

.

Generalized Convexity

Let

.

.

Examples

-

(CO Example 3.47)

Let.

Thenis

-convex iff:

is convex and for all

and

, there holds

which holds iff

for each, i.e., iff

is component-wisely convex.

-

(CO Example 3.48)

A functionis

-convex iff :

is convex and for all

and

, there holds

N.B.:.

-

this is a matrix inequality and

-convexity is often called matrix convexity.

-

is matrix convex iff

is convex for all

.

-

The two functions

are matrix convex.

-

this is a matrix inequality and

Basics of Optimization Problems

General Optimization Problems

By an optimization problem (OP) we mean the following:

the objective function;

the optimization variable or parameters;

,

, the inequality constraint functions; and

,

, the equality constraint functions.

.

Feasibility

Consider an (OP) as above.Feasible point: those

Feasible problem: A problem with nonempty feasible set, i.e.,

Infeasible problem: A problem with empty feasible set; i.e., there are no

Remark.

-

A feasible problem need not have a solution; e.g.,

has no minimizer nor minimum on

.

- An infeasible problem never has a solution–there are no parameters

to even test.

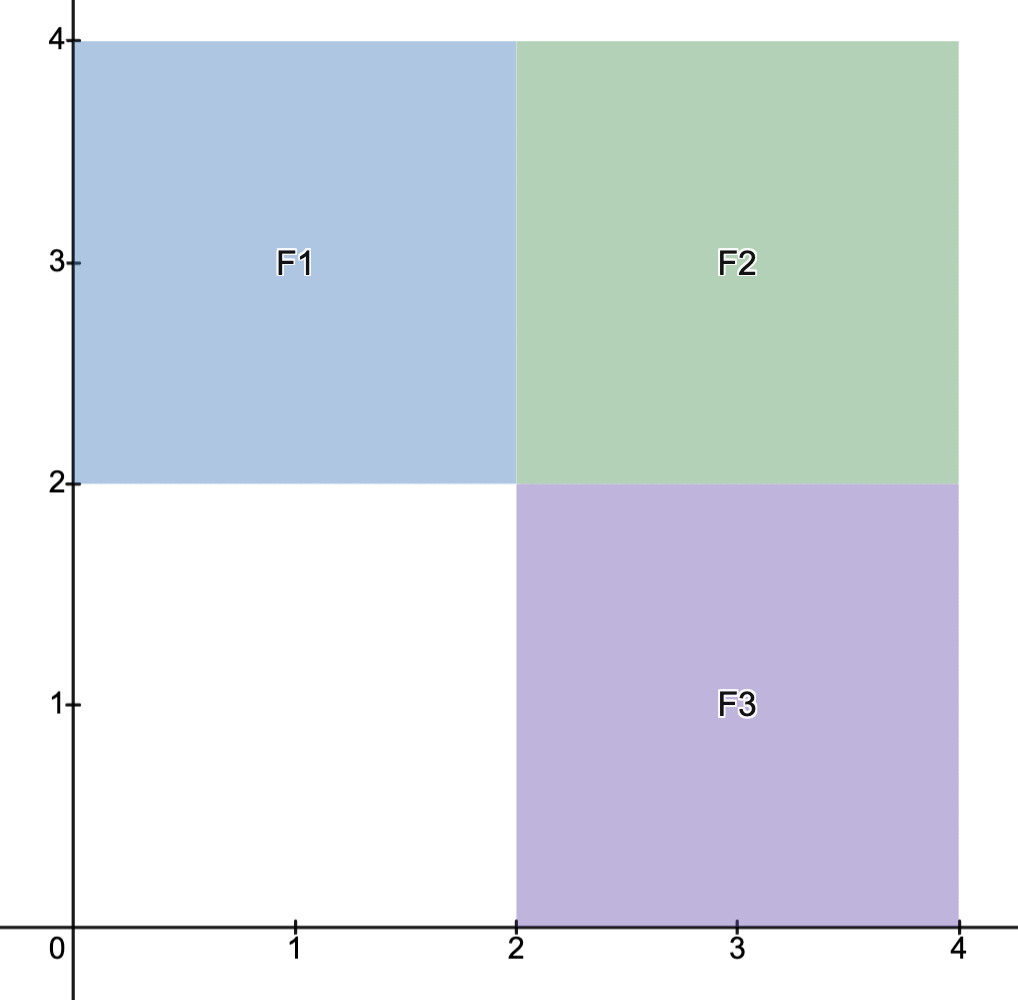

Basic Example

Consider the problem

The objective function is

,

The inequality constraint functions are

.

The domain of the problem is

.

The feasible set:

Let

.

Note that the darkest region given by

Can we solve the problem?

Noting-

as

approaches a point on the circle

, and

- such sequences exist in the feasible set,

The Feasibility Problem

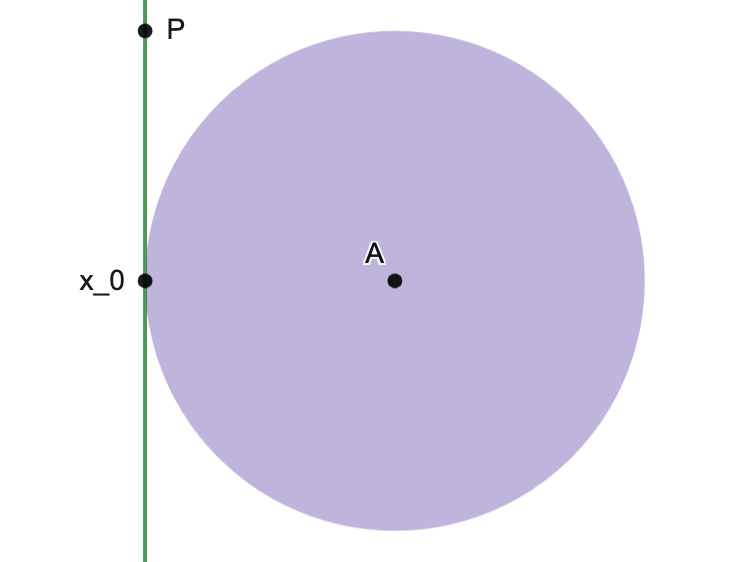

Feasibility problem: Given an (OP) with

Example 1.

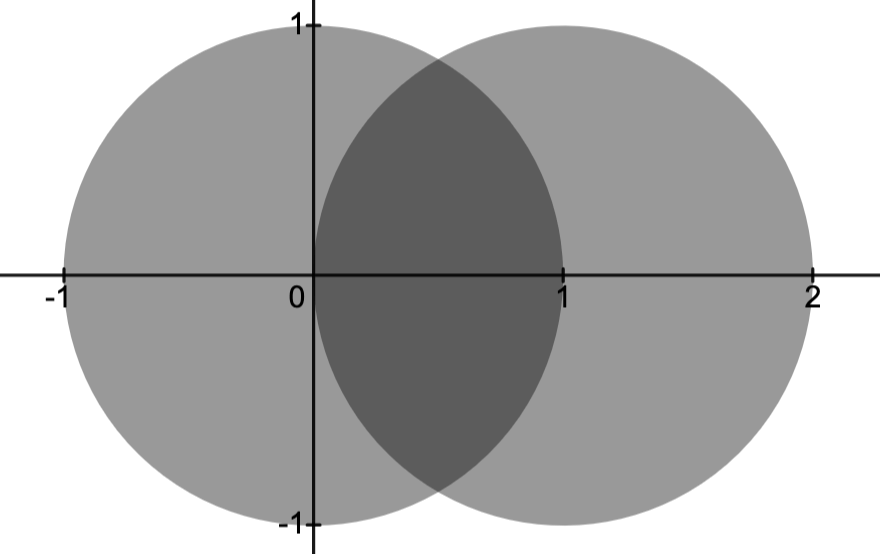

The problem

This is depicted below.

Optimal Value and Solvability

Recall:

Optimal value:

The value

,

N.B.:

Solvable:

When the problem satisfies

there exists with

,

Remarks.

-

iff the (OP) is solvable.

Indeed,is not well-defined unless the (OP) is solvable.

-

need not be finite:

if

is unbounded below on the feasible set; and

if the OP is infeasible.

Standard Form

Optimization problems need not be placed in the form we defined them.We therefore introduce the following definition.

(OP) in Standard form:

Example: Rewriting in standard form.

We can recast more general optimization problems in standard form; e.g., consider

(noting

)

for

for

Equivalent Problems

Suppose we are given two OP’s: (OP1) and (OP2).We say (OP1) and (OP2) are equivalent if: solving (OP1) allows one to solve (OP2), and vice versa.

N.B.: Two problems being equivalent does not mean the problems are the same nor that they have the same solutions.

Example.

Consider the two problems:

minimizes

on

minimizes

on

,

Indeed, if we find the solution

Change of Variables

SupposeThen, under the change of variable

Moreover, injectivity may be dropped.

Justification.

Indeed,-

if

solves (OP1), then

solves (OP2).

(More generally,such that

solves (OP2).)

-

if

solves (OP2), then

solves (OP1).

Example

Consider the problem

.

.

Eliminating Linear Constraints

LetLet

Then

Consequently

Justification.

Indeed,- if

solves (OP1), then any

with

solves (OP2), and

- if

solves (OP2), then

solves (OP1)

Example.

Consider the minimization problem

But, to match with above: let

.

.

Therefore, the minimization problem becomes

Thus, the original problem has solution

.

Slack Variables

GivenUsing slack variables

Remarks.

-

All of the

which may satisfy the constraints of (OP2) are the same as those which satisfy the constraints of (OP1); this justifies the equivalence.

-

Let

be the feasible set of (OP1) and

that of (OP2).

Thenand

; i.e., the feasible sets are not the same object.

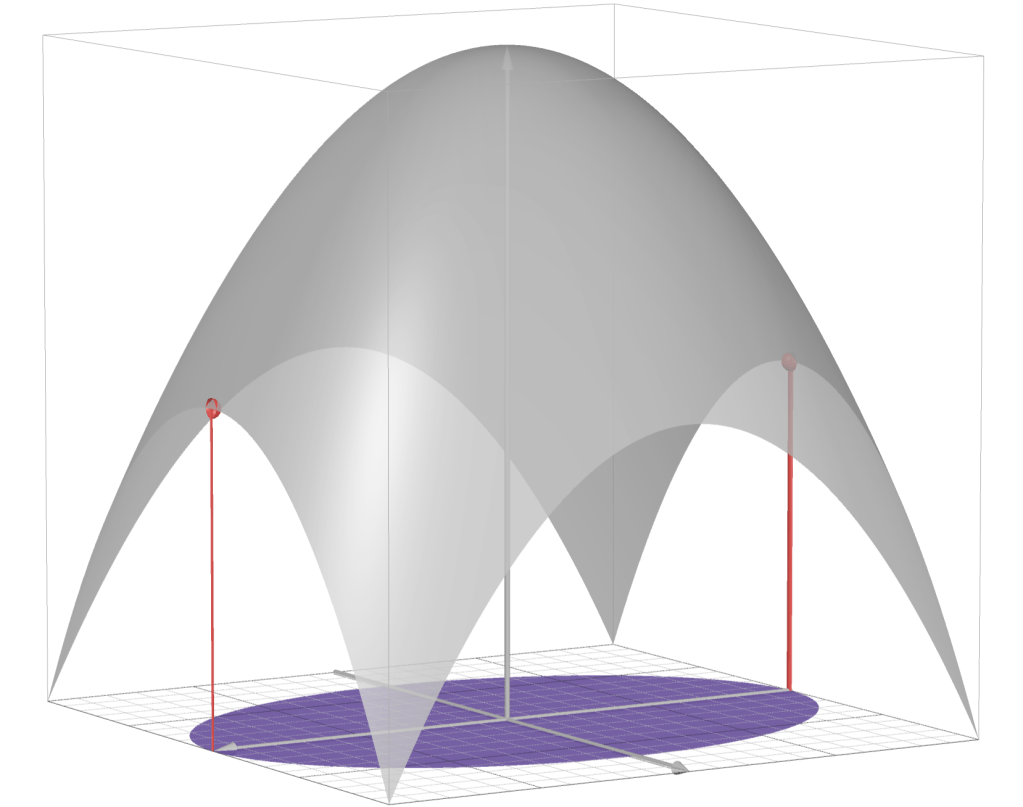

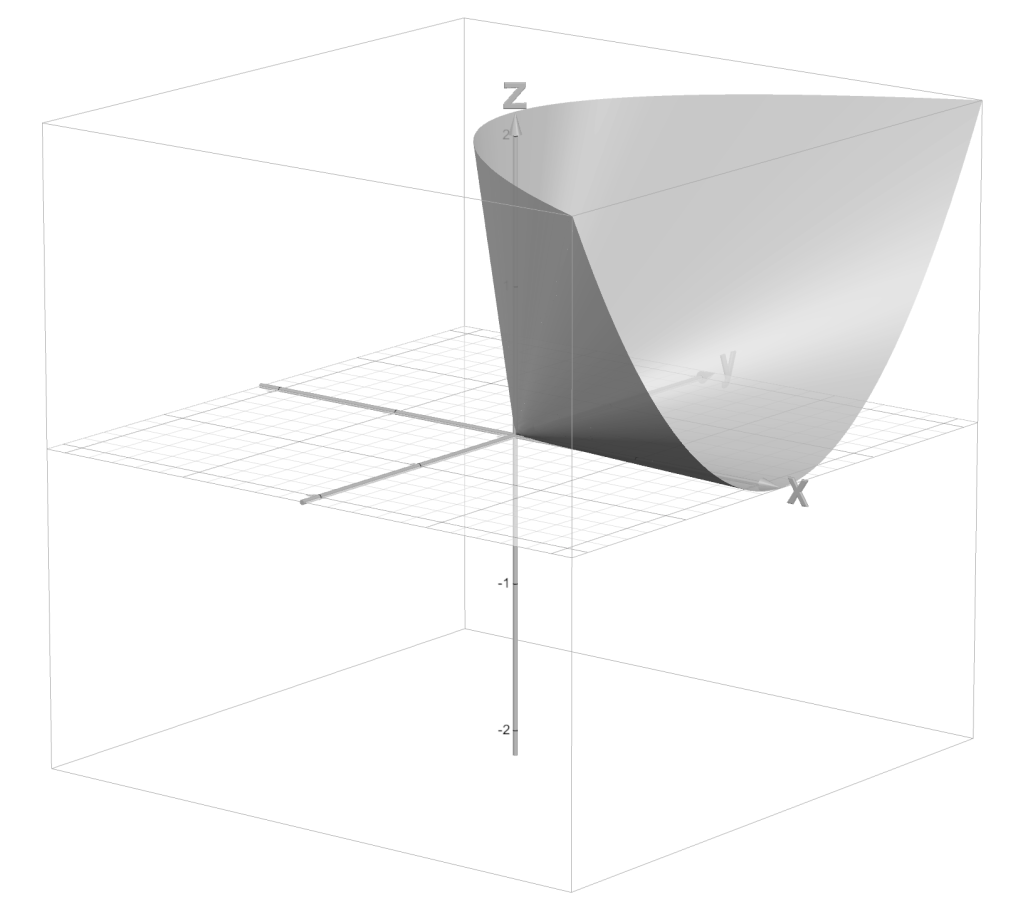

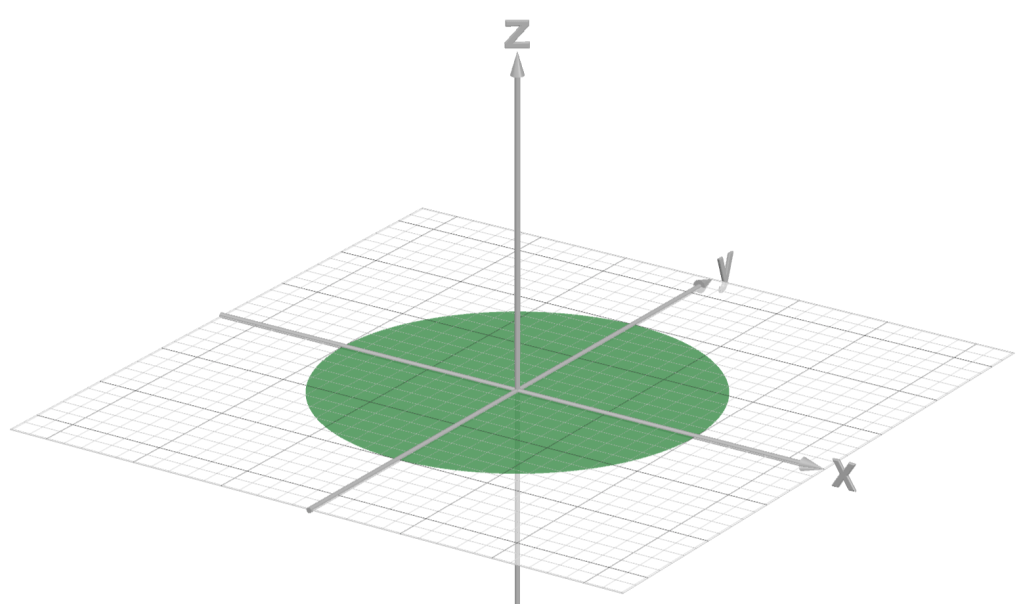

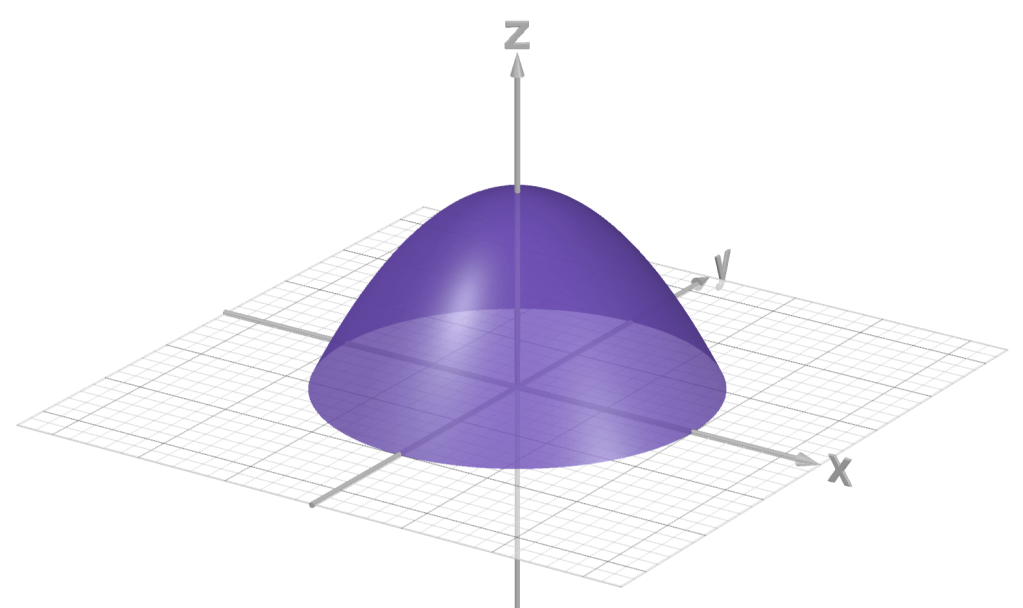

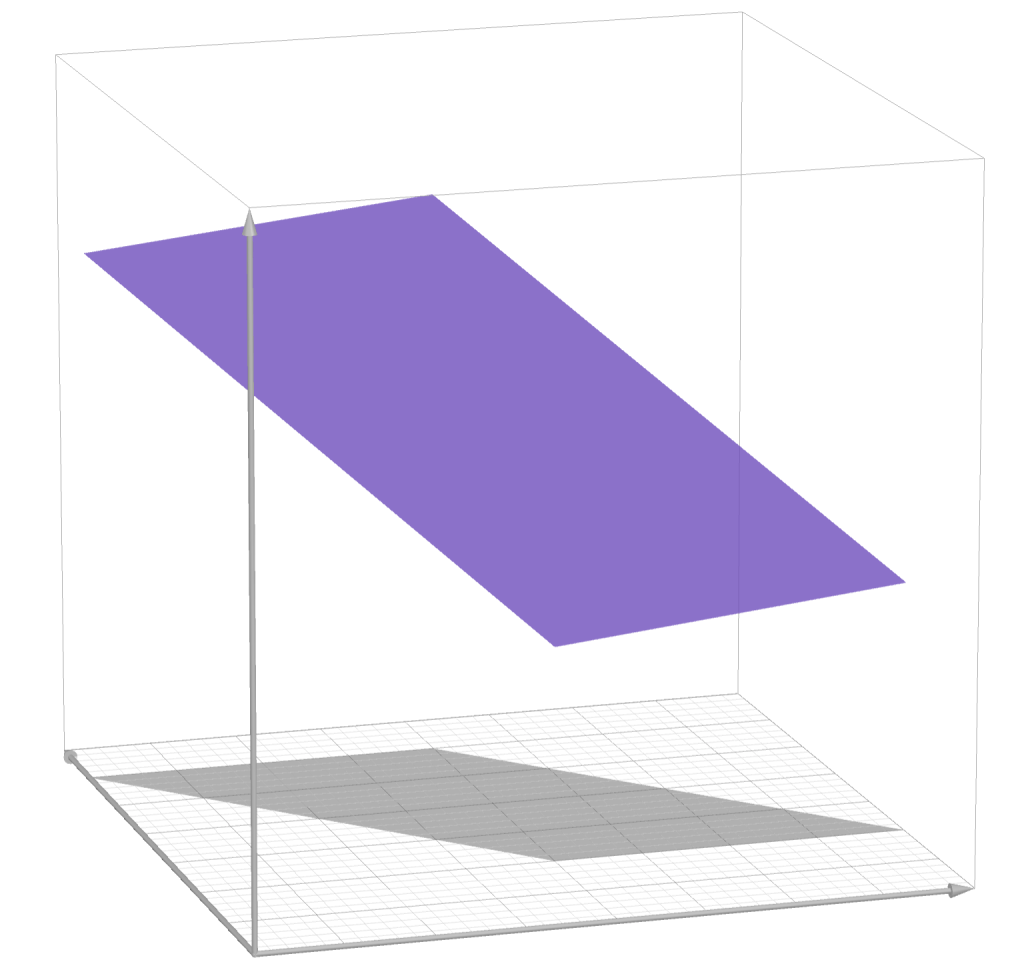

- Example: in the images below, the disk depicts a feasible set

and the paraboloid-type set depicts the feasible set

with slack variable

.

N.B.: the permissiblecoordinates are the same for both sets.

Main point:

Solving the system of equations

Example.

Consider

.

Moreover, one can solve the problem

Epigraph Form

Recall:The optimization problem

Fragmenting a Problem

Proposition. Given

.

Viz., to minimize a function on a set

Example.

Consider the (OP)

Using the preceding proposition, the optimal value of (OP) is given by

.

Basics of Convex Optimization

Convex Optimization Problems

Abstract convex optimization problem: A problem involving minimizing a convex objective function on a convex set.Convex optimization problem: a problem of the form

-

and

are convex; and

-

and

are fixed.

Some Remarks

Remark 1.

As defined, a (COP) is an (OP) in standard form; naturally, there are nonstandard form (OP)’s equivalent to (COP)’s.E.g., the abstract (COP)

.

Remark 2.

We emphasize: the equality constraints are assumed to be affine constraints.Moreover, the equality constraints

,

.

Remark 3.

The affine assumption on the equality constraints can be lifted at the possible expense of an intractable theory/numerical analysis.E.g., if

Remark 4.

Generally,Remark 5.

The common domain

Optimality for Convex Optimization Problems

Assume throughout thatProposition 1. If

Proof.

We will follow a proof by contradiction; i.e., we will show that assumingStep 1.

Step 2.

SupposingBy choice of

Step 3.

Set

It follows that

Step 4.

Since

.

.

Proof.

Step 0.

N.B.: since

.

Step 1.( )

)

Suppose

Set

Using

,

Since

Additional justification

SinceStep 2.( )

)

Supposing

.

Proof.

By Proposition 2., we have that

Differentiability of

.

Some Examples

Example 1.

Let

.

C.f.,Convex Function Theory.Second Order Characterization. By the preceding corollary, we have

.

Three cases:

is unbounded below and hence (OP) is unsolvable;

is invertible and so

is the unique solution to (OP);

and

has an affine set of solutions.

Example 2.

Let

.

Two cases

is an inconsistent system

the problem is infeasible.

is a consistent system; then

,

for some

.

In case 2., we have

and

.

for all

,

.

.

Linear Programming

Linear program: a (COP) of the form

,

Recall ( ):

):

For

.

Different than:

Determining the Feasible set:

Step 1. ( )

)

Given

Step 2.

Given

Step 3. ( )

)

Given

Step 4.

Steps 1. and 3. imply the feasible(c.f. Convex Geometry.Polyhedra.)

Example.

Let

Remarks.

-

Given

, have equivalent problem with objective

.

Indeed,

WLOG: can assumeto solve problem.

-

Since

one also calls the problem of maximizingover a polyhedron a (LP).

Example: Integer Linear Programming Relaxation.

Integer Linear Program: an (OP) of the form

N.B.: An (ILP) is not a convex problem, but may be approximated by one (see below).

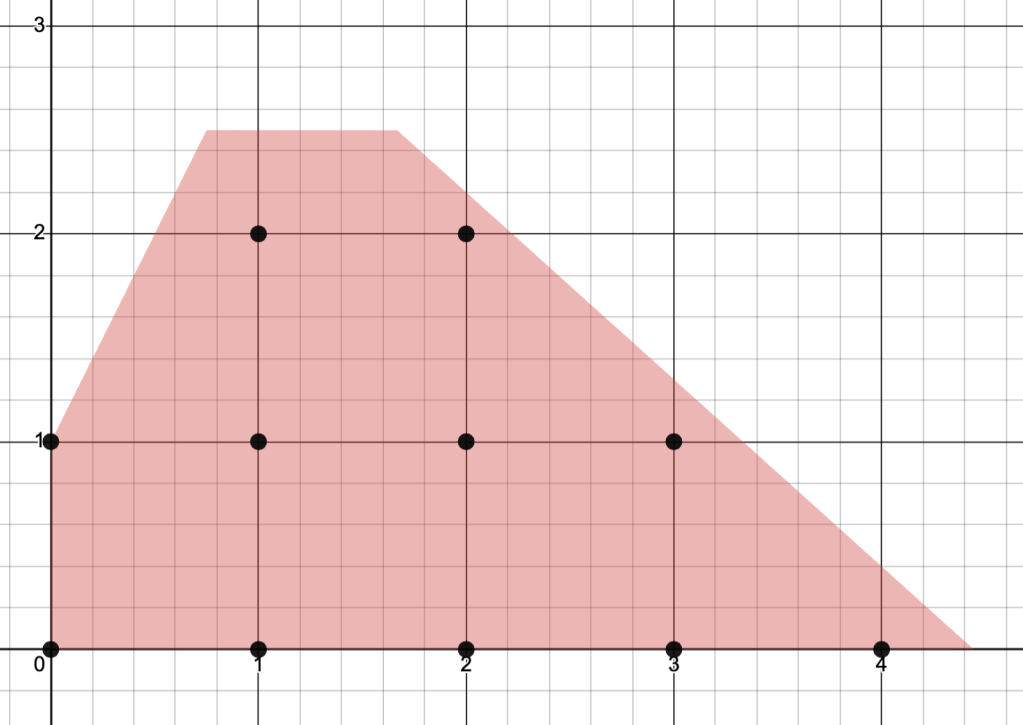

The feasible set

Let

Then

.

Example. Consider an (ILP) with constraints given by

Remarks.

-

Can of course also impose equality constraints

:

-

If we impose

, then the problem is called a boolean linear program:

Suitable for when coordinates ofindicate when something is “off” or “on” or decision is “no” or “yes”.

Can also useinstead.

Relaxation of (ILP)

The LP

Important points:

-

The “tightest” convex relaxation is given by

Generally speaking, finding the convex hull is not an efficient way of approaching (ILPs). - The relaxation (LP) of (ILP) is generally easier to solve, though exact algorithms exist for (ILP).

-

If

then.

(Indeed the relaxation has larger feasible set.) -

If

solves the (LP), then it solves the (ILP).

Relaxation of (BLP)

Explicitly, a (BLP) is of the form

N.B.: the relaxation

.

Example.

Problem Given- assign each worker to work at some location

- assign at most one worker to a location

- minimize cost of operation and transportation

Construct objective function

We find

Construct constraints

The constraint that

Since each worker is selected only once, we have

.

Formulate Problem

Putting everything together, the (BLP) formulation of the problem is

Quadratic Programming

Quadratic program: an (OP) of the form

Remarks.

-

As for (LP), the constraints

describe a polyhedron.

-

Given

, then

WLOG: can assumeto solve problem.

-

If

then,

Thusimplies

is convex.

N.B.: The factoris just a convenient normalization.

-

The generalization

results in quadratically constrained quadratic programming (QCQP).

Imposingensures the (QCQP) is convex.

(C.f., Convex Function Theory.Level Sets.)

-

The generalization

also results in a (QCQP), but this can break convexity.

E.g., The quadratic constraints

result in a (BLP) since these constraints enforceor

, respectively.

-

There holds

-

The assumption

(i.e.,

) is not a serious restriction.

Indeed, first note that, sinceis a scalar, we have

.

Let.

Thus,

where.

Lastly, observe the symmetry of:

.

Thus every quadratic

has a “symmetric representation” of the formwith

.

Example: Least Squares

Least squares: an unconstrained (QP) of the form

Features:

-

WLOG: may assume columns of

are linearly independent, and so

.

-

N.B.: a least norm solution to (LS) is generally given by

where,

is the pseudo-inverse (aka Moore-Penrose inverse) of

.

-

Under the WLOG assumption, there holds

.

Recall (definition of  )

)

For

.

Rough Justification of WLOG

Let

Therefore, we may write

.

Computing

.

Therefore, a (LS) problem with matrix of size

This argument holds in general: if

Remarks.

-

If

has solution

, then

solves the (LS) problem.

-

If

has no solution, then any

solving the (LS) problem gives a “best” estimate solution to

, where “best” is chosen to mean in terms of the vector norm

.

-

While minimizing

is equivalent to minimizing

, the exponent

ensures

is differentiable (at

).

(C.f.:is not differentiable at

, but

is.)

Solving the (LS)

Step 1. (The problem is convex)

The objective function

.

-

and so

, i.e.,

is symmetric;

-

for all

there holds

i.e.,,

.

Step 2. (The critical points)

We compute

.

Step 3. (The solution)

By corollary proved above:Moreover,

- linear independent columns

iff

.

.

- Since

is square, can conclude

is invertible.

Lastly: since

iff

.

Example: Distance Between Convex Sets

LetNearest Point Problem (NPP): Among

The (NPP) may be expressed as a standard form (COP).

Indeed, supposing

When the

Indeed, supposing

Polyhedral Approximation.

Let

Geometric Programming

Monomial function: given

,

.

,

Remarks.

-

Let

Since any monomial is a posynomial, we have.

-

If

then

Thusis a group and

a “conic representation” of

.

-

As usual, we use the language “writing in standard form” to refer to writing an equivalent (OP) written in the form (GP) above.

General (OPs) clearly equivalent to a (GP) may be called a geometric program in nonstandard form.

For example, the geometric program

with

is readily rewritten as a standard form (GP):

Rewriting (GP) as a (COP)

General (GPs) are not convex (e.g.,However, any (GP) is easily recast as a (COP) via change of variable.

Step 1. (The change of variable)

We will write

Step 2. (Monomials  convex function)

convex function)

Let

convex

convex

Step 3. (Posynomial  convex function)

convex function)

For

Step 4. ((GP)  (COP))

(COP))

We explicitly write the (GP) as:

Step 5. ((GP) in convex form)

At last, since exponentiation may result in unreasonably large numbers, it is customary to take logarithms, resulting in the geometric problem in convex form:

-

Concavity of

is too weak to break the convexity of

, and so the problem is still convex.

-

The constraints are equivalent since

is monotonic and injective on

.

Example.

(Taken from Boyd-Kim-Vandenberghe-Hassibi: A tutorial on geometric programming)Problem Maximize the volume of a box with

- a limit on total wall area;

- a limit on total floor area; and

-

upper and lower bounds on the aspect ratios

and

.

The volume of the box is

.

Construct contraints

Putting everything together, we realize the problem may be formulated as the following (GP):

Semidefinite Programming

(Heavily influenced by Vandenberghe-Boyd Semidefinite Programming.)Linear matrix inequality (LMI): given

.

Semidefinite program (SDP): an (OP) of the form

Convexity of Feasible Set.

To see that (SDP) is a convex problem, first note: if and

.

.

Example 1. LPs are SDPs

Consider the (LP)

Given

Since

.

Letting

,

.

Therefore, using

Therefore, defining

.

In conclusion, we have that the (LP)

Example 2. Nonlinear OP as a SDP

Consider the nonlinear (COP)

N.B.:

-

choice of domain (a halfspace) of objective and ensures convexity.

-

concave problem.

.

.

.

Indeed, evidently,

and

.

.

To make it clearer, introduce the notation

Lagrangian Duality

Throughout, let (OP) denote a given optimization problem of the form

Recall:

The Lagrange Dual

Lagrangian: the function

.

Lagrange multipliers: the variables

The vectors

Lagrange dual function: the function

.

N.B.: as an infimum of affine functions,

Proposition. For

,

,

Proof.

-

Let

be feasible.

Then

-

Let

and

be arbitrary.

Then feasibility ofimplies

Consequently,

-

Therefore, for all feasible

, for

and for arbitrary

, there holds

and so

(Indeed,.

is a lower bound of

and

is the greatest lower bound of

.)

Lagrangian as underestimator.

(See CO 5.1.4)

Define the indicator functions

N.B.: if

.

In particular, for each

Example 1

Consider the least squares problem

.

.

Therefore, the Lagrangian

N.B.:

Consequently,

,

In conclusion,

Example 2

Consider the linear program

.

-

equality constraints given by

.

-

iff

iff.

Therefore, the Lagrangian for (LP) is

Want to compute

Therefore,

.

Therefore, the Lagrange dual is

In particular, for dual feasible

Return of Conjugate Function

Recall: given

Consider the the (OP)

The Lagrangian is

We may now compute the Lagrange dual in terms of the conjugate

,

Appendix

Differentiating

Given

,

.

Differentiating

Given

.

.

Example.

Let

Differentiating

Given Using the Taylor expansion

.